I was waaay too young when I first picked up a true crime book.

At 10 years old, I was a typical voracious reader. I annoyed the crap out of my teacher as that one kid who had to have extension activities because the regular tasks weren’t enough to keep her quiet for long enough. So extra reading, often in peculiar places, was my jam.

We were doing a whole-class project on Edwardian England, co-creating a wall display of drawings, boxes of text, headlines, photocopied images highlighting historical events. The teacher asked me to “find out all you can” about a new technology of the era, wireless telegraphy.

Dry, factual, technical, right? The perfect “go away and leave the rest of us alone” assignment for the resident nerd. Off I went to the school library to dip into the encyclopedia (this was in olden, pre-Internet times).

Marconi’s invention pops up in Dracula as state of the art tech. By 1910, it was in wide use and, on June 24 of that year, the U.S. government passed the Radio Ship Act, making it compulsory for all transatlantic steam ships to carry radio communications equipment. So, the encyclopedia entry included a sidebar about ‘demon doctor’, Hawley Harvey Crippen. The following month he became the first murderer whose arrest was co-ordinated via international telegraph messages.

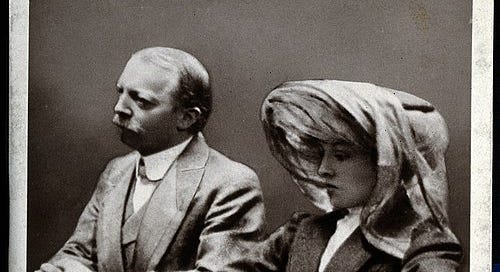

At the beginning of 1910, Crippen and his wife, Cora, were Americans living in Camden Town. Cora disappeared at the end of January, supposedly traveling to the USA to care for a sick relative. Within a week or so, Crippen pawned her jewelry, and, in mid-March, moved his mistress, Ethel LeNeve into her bed. When Cora’s friends asked after her, Crippen told them she had died suddenly, in “some little town in San Francisco”. As if no one would become suspicious.

Between March and July he played house with Ethel, who swanned around London in Cora’s clothing (including her prized furs) and remaining jewelry. Although it’s never been clear how much Ethel knew about what happened to Cora, Crippen believed he’d got away with uxoricide. However, in July, after prompting from Cora’s friends who felt Crippen’s account just didn’t add up, Inspector Dew of Scotland Yard eventually came knocking. The first time, he only asked questions. But it was enough to make the couple flee.

If only they’d had the balls to stay put. Running is a sign of guilt. The police investigation went into overdrive and a search of the home uncovered human remains under the cellar floor, triggering a media frenzy. The lovers made it to Antwerp, where they purchased male clothing to disguise Ethel as a young man. ‘Mr Robinson’ and his oddly curvaceous adult son boarded the SS Montrose, on an 11 day voyage to Canada. Again, as if no one would become suspicious.

Ethel’s disguise failed to convince the Montrose’s captain, Harry Kendall, who had a hunch his passengers were actually London’s current Most Wanted. He telegraphed back to shore. Dew, pulling a stunt that can only be described as thirsty, hopped on a faster steamer, the SS Laurentic, and was waiting for the fugitives on the gangplank as the Montrose docked in Quebec City. To the delight of the assembled tabloid journalists, he greeted his quarry with handcuffs and a brisk “Good morning, Dr. Crippen.”

It’s a Story. And even back then, it set my Story Senses twitching. I wanted more information than the encyclopedia sidebar offered. So I went to a second location. I’d recently learned how to use the card index at the town library. At the time, under-13s weren’t allowed to borrow adult books, but there was no rule that said we couldn’t browse the main section, and take out books on Mum’s ticket because Gen X levels of parental supervision. How else was a Haunted Generation going to learn how to scare itself?

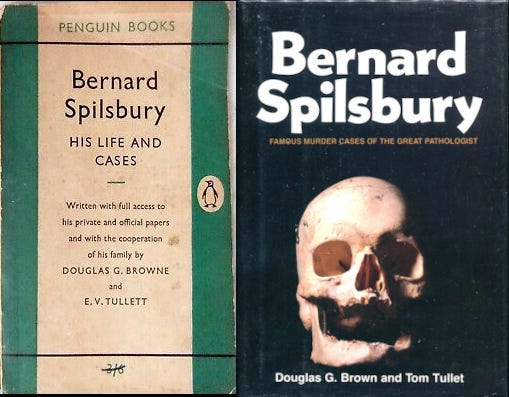

I located “Crippen, H.H.” In the aptly named morgue and was sent to a shelf I’d never explored before: Dewey number 364 (criminology). The book the card index sent me to was this one, this exact edition with the lurid skull cover rather than the much more academic-looking Penguin original.

One of my character traits is morbid curiosity, so I already knew I liked books with skulls on the front. I’d picked up a few Pan Books of Horror Stories at jumble sales and read them under the bedcovers at night. (Thank you, Herbert Van Thal, for this early and comprehensive introduction to the genre).

But the Spilsbury book was different and scratched my itch to acquire “information about danger or threats” in a new way. For a start, it was non-fiction, something I’d never read before, about real, if long-dead people, real pain, real horror, real, messy lives.

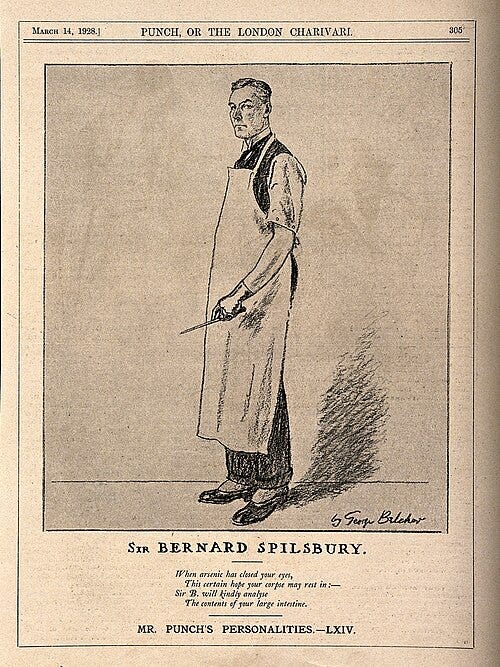

In the first couple of chapters, I learned about a young man growing up not far from my hometown in Warwickshire who went on to define his profession, pathology, in the early years of the twentieth century. Bernard Spilsbury emerged into the spotlight during the Crippen trial, impressing both the court staff and the jury with his clean-cut, firm-jawed looks, a red carnation in an impeccably tailored suit jacket, and the same ineffable Oxford-educated white guy authority that commanded even the furthest outposts of the British Empire.

He stepped onto the witness stand in the Old Bailey more than ready for his close up. In fact, he’d brought a microscope and slides with him, and went on to show the jury, in intimate detail, a section of skin that, the Crown argued, proved the remains belonged to Crippen’s wife.

The prosecution’s case hinged on a horseshoe shaped mark on said skin section, which Spilsbury argued came from the oophorectomy performed on Cora Crippen years before. This was a crucial identifying mark as the remains in the cellar consisted of scraps, lumps of tissue, no bones, no head or fingerprints, one hank of bleached blonde hair wrapped around a curler, and fabric from a man’s pajama jacket. It would have to have been one hell of a coincidence that Cora disappeared then subsequently random pieces of human flesh were discovered in her husband’s cellar, but a lively defence lawyer might have leveraged ‘reasonable doubt. Until Spilsbury, an expert in identifying scar tissue, informed the court the scar positively identified the skin flap as belonging to the victim.

Crippen was convicted and hanged in Pentonville, on November 23rd 1910.

For my assignment, I wrote about the murder, chase, trial and execution, probably three or four non-paragraphed pages. My teacher was horrified but pinned it to the wall display anyway. I can bet you hard cash dollars that none of my classmates even looked at it. My first true crime article was binned at the end of term with the rest of the material.

Nonetheless, I’d discovered a new interest.

Over the next few years, I burned through the 364 shelf of the local library. Some books I liked (Keith Simpson’s “Forty Years of Murder” remains a problematic fave), some of them I didn’t. True crime as a genre can be simultaneously too much and never enough. The worst examples go hard on salaciousness and crude anatomical description, dwelling on the butchery rather than the cause. Too many writers take an authoritarian tone, adopting the perspective of the savant cop (or pathologist) whose technique should not be questioned and whose intrinsic rightness makes the perpetrator wholly wrong. There’s a disdain for victims too, especially women, who are flattened within a Madonna/Whore paradigm, with those categorized as whores somehow complicit in their own demise.

The accounts of the Crippen case I read back in the 1980s leaned hard into victim-blaming, evincing a strange romantic sympathy for the man who dismembered his wife so he could run away with his mistress. They permit the dead woman no more dimension or agency than the samples of her tissue on Spilsbury’s microscope slides. In their biography of Spilsbury, Browne and Tullett regard Cora Crippen as an obstacle to her husband’s self-actualization, mocking her music hall career and describing her as “his common, pleasure-loving, rather slatternly wife” (p.39) who refused sex. No wonder he tired of her, amiright?! A level of misogyny that alienates female readers of any age.

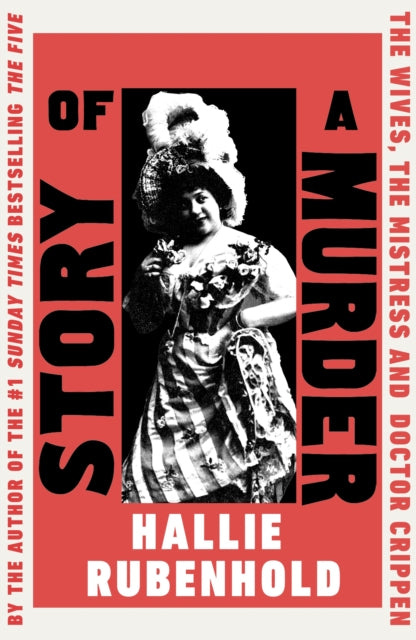

So, I’ve been waiting decades to read Hallie Rubenhold’s Story of a Murder: The Wives, the Mistress, and Dr. Crippen. As she did with her exploration of the women who died at the hands of the Ripper, The Five, Rubenhold counterbalances a century of reductive writing and presents a full portrait of the victim’s life, cut short, and the impact on others of her death.

Cora Crippen, neé Kunegunde Mackamotzki, aka Belle Elmore was born in Brooklyn in 1873. She met Crippen in 1892, when she was living in an apartment paid for by a married man–and pregnant. It appears she first encountered her future husband when he assisted at her illicit abortion.

Crippen dazzled the grateful, vulnerable teen with his doctor-ish credentials, grooming her from the get-go to be his second wife. He knew her shame about her secret abortion, so he controlled her psychologically. He controlled her physically too, manipulating her into an oophorectomy. Crippen wanted to make sure there were no children from this union.

He didn’t care that the procedure pushed Cora into early menopause. He didn’t care it left a jagged scar, although this would ultimately be what condemned him to the gallows. It was perhaps inevitable that he would one day want to be rid of her, and that his weapon of choice would be a coldly planned and executed dose of poison.

Sorry, Sir Bernard Spilsbury and all your successors, including the cast of CSI in the 21st century, but the story of a murder can’t be told simply by examining a corpse. A murder happens near the end of the story, and I’m intrigued by the beginning.

Rubenhold goes beyond the pathologist’s casebook to lay bare the minutiae of the everyday lives that intersect across a murder site, often working and lower middle class lives otherwise passed over by historians. She tracks the origins of the crime by digging into the personal history of each member of the fatal love triangle, tracing Crippen’s wanderings across the USA, hopping from job to job, outlining the ambiguity around what happened to his first wife, his history of callousness and love of easy money, and tracking his collision course with a pretty, ambitious typist with aspirations above her social class. Crime aside, it’s a fascinating study of late 19th century immigration and the working lives of Edwardian Londoners.

I wish my teen self had been able to pick up Story of A Murder. But perhaps I needed to read the misogynistic and problematic tomes on the 364 shelf first, in order to appreciate Rubenhold and her ilk, and to seek out more nuanced and humanizing accounts. This is the kind of true crime book that assuages my morbid curiosity these days—one without a skull on the cover.

What’s your true crime origin story? Drop a comment below or head over to our chat.

I’m not going to turn on paid subscriptions. However, I’m working for tips in 2025 and am still eternally grateful to those who cross my palm with silver. Rather than forking out $5/month, how about a one-off gesture of appreciation if a particular article tickles your sweet spot? Why not buy me A Soothing Cup of Tea via PayPal? Or, if you want to support my cat rescue work, you can always donate a Chewy gift card to karinawilson@substack.com. THANK YOU!