The ninth entry in the 45 year-old Alien franchise opens this weekend. Even though I can guess what happens (foolish humans poke around where they shouldn’t and get a faceful of space parasite), I still bought tickets with friends weeks ago. I’m right there with Bri.

Why do xenomorphs fascinate us so much?

Visually, they trigger an electric jolt of recognition. They’re simultaneously familiar and wondrous strange, the epitome of Freud’s ‘Unheimlich’. We know them, yet we don’t, so we’re compelled to learn more, to lean over and peer into the pulsating egg sac. That’s how they get you.

Much of the adult xenomorph’s menace derives from their ‘Other’ qualities. Unmistakably alien, they still echo mammalian physiognomy in key details of their construction (torso, spine, arms, legs, phalanges) while also being somehow reptilian and insectoid. They possess a carnivore’s teeth, two sets, and rapacious claws. Their sleek black heads resemble a weaponized penis, a tumescent harbinger of the violence, anxiety, and bloodshed of human birth. Those heads tilt on flexible necks similar to ours, evolved to pivot a heavy weight atop a vertical body. Once that head tilts in your direction, it’s over. The xenomorph will catch you and make you holler louder exiting this existence than you ever did entering—even if, in space, no one can hear you scream.

This monster, unlike most other cinematic fiends, did not begin life as words on a page. It began in the imagination of visual artist and sculptor, Hans Ruedi Giger who, by the mid-1970s, had developed a unique style, rendering biomechanical figures that tapped into twentieth century industrial and military horror. From the outset, he traveled a haunted path. Giger (born in 1940) grew up under the shadow of the Nazis and the Cold War in Switzerland. He was a sensitive child, attuned to the fears of those around him, of past iniquities rising again, or worse, a future burning nuclear hot. From an early age, he spent time in contemplation of dark and terrible things. According to his second wife, Carmen Giger, when Hans was five years old his sister took him to a local museum.

“Down in the cellar was the mummy of an Egyptian princess, with blackened bones still covered in patches of skin. His sister laughed at him because he was so frightened but he told me that he went there almost every Sunday after that, alone, to sit with the mummy. That experience accompanied him all his life, and those themes: the black abyss of the cellar, the bones and Egyptian culture influenced his work massively. If you look at the monster from Alien, it’s not only black, with bones protruding from under the helmet, but it has this elongated head that you see throughout Egyptian culture.”

Giger, much to his parents’ chagrin, was an academic failure. He spent his adolescent afternoons shooting guns at a local dump site and was eventually expelled from school. A stint in the army cured him of his weapons obsession, and, aged 18, he began an apprenticeship as a draughtsman. His new employer worked mainly for the Catholic Church, so Giger became adept at designing and drawing religious artefacts. He sought therapy via his art. He dove deep into Freud and Jung and used their tools to probe his own unconscious and to haul the creatures he found roaming there into the light of day. After he, crucially, learned how to use an airbrush, art therapy became his life’s work, a meshing together of his lived trauma (especially his birth trauma, which he claimed to remember) with surrealist and fantastical influences from Hieronymus Bosch to Salvador Dali and Ernest Fuchs to Native American and Ancient Egyptian mythologies.

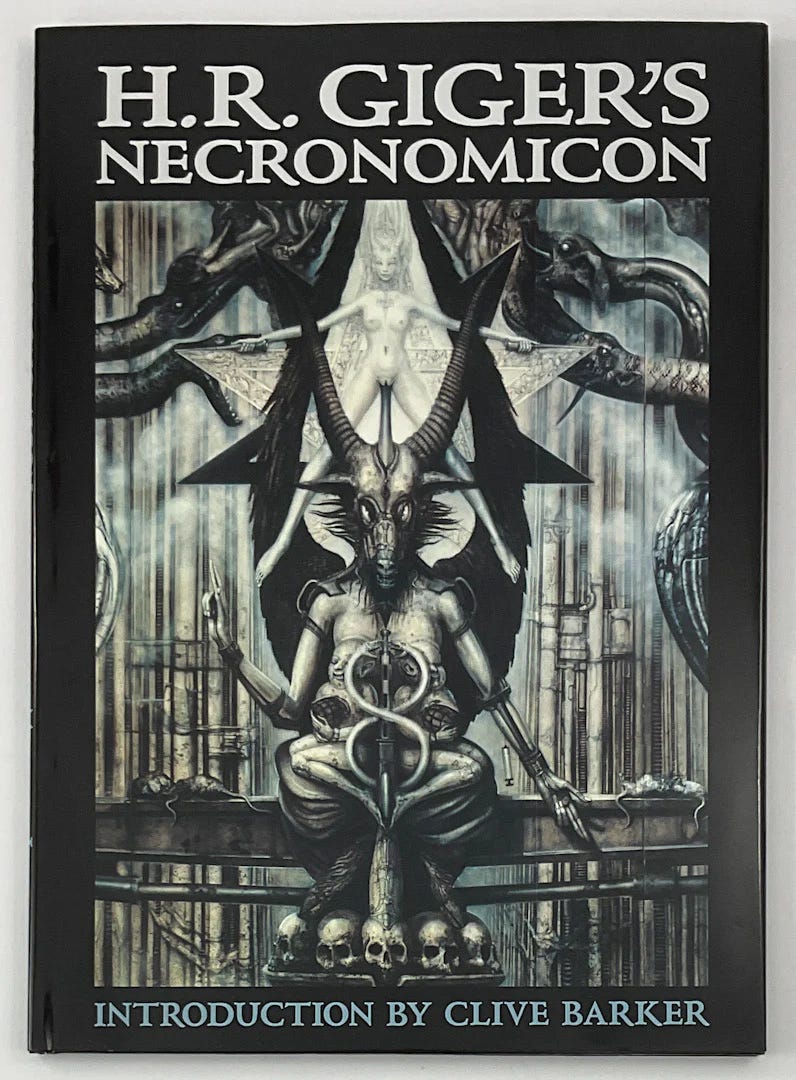

The title of Giger’s masterwork, Necronomicon (1977) nods at the Lovecraft mythos and the cursed book supposedly created by “the legendary madman Abdul Alhazred”. However, Giger’s images go beyond the depiction of cosmic monsters. In his ‘Biographie’ section, he says (and please excuse my—or rather, Google’s—German translation):

“whenever I deal with the subconscious, the same formal elements appear which, on the surface, I use in a purely formal way, but which through their frequent appearance, give reason to search in almost forgotten, apparently unimportant, past events.”

Giger digs into his memories, conscious and unconscious, for his monsters’ origin stories. He recalls childhood dreams of “huge, infinitely deep shafts. Steep, breakneck wooden stairs without railings led along the walls into these gaping abysses.” He frames himself as a haunted child, one who channeled his “inclination for the morbid and fantastical” into constructing a ghost train to entertain the neighborhood.

“I made human skeletons out of cardboard, wire and plaster, which I then illuminated in different colors using flashlight bulbs. Some of my little friends were put in white sheets and others secretly moved a mechanism that lifted a coffin lid, swayed a man hanged from a branch, or opened the doors of a giant monster. The visitors to my ghost train, mostly boys and girls from the street, were ushered through this witches’ cauldron on a cart that ran on ball bearings, steered from behind, for a fee of 5 centimes…[the gate] had two wings, covered in sheet metal and painted with snakes, bats, and skulls. Two rubber tires were nailed to the lower edge [of the gates] so the cart could be driven straight into the closed gate. It opened with a loud bang and the curious child already regretted sitting in the cart… The children were frightened by all means and some of them ran home crying.”

Despite this early demonstration of showmanship, Giger’s creative life was not all carnival fun and games. He struggled with depression and, as a young man, experienced bouts of mental illness. Necronomicon also charts his grief in the wake of his partner Li Tobler’s death by suicide in 1975. They had been together, off and on, for nine years. They lived in a series of bug-infested apartments in Zurich, where Giger dreamed of monstrous toilets that threatened to castrate him, and of giant grey worms (a lifelong source of repulsion) birthing themselves through his mouth. Li was his muse, posing for drawings when alive, and haunting him after her death at the age of 27. Her face shimmers at the center of images on page after page of Necronomicon.

In 1973, Giger designed the cover for Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s Brain Salad Surgery, which brought attention from a wider global audience, and the publication of Necronomicon made him a household name—in key households. Screenwriter Dan O’Bannon was a fan.

Giger was already in the mix for the creature design for Alien before Ridley Scott came on board, but Twentieth Century Fox executives were reluctant to commit until they confirmed a director. When Scott signed on, and saw the visceral power of Giger’s images, he was instantly convinced.

"Dan O'Bannon came in with a copy of H.R. Giger's Necronomicon and said, "What do you think of this?" I nearly fell over", "Scott said. "I started leafing through it until I came to this one half-page painting and I just stopped and said, 'Good God, I don't believe it. That's it. I'd never been so certain about anything in my life. I thought we would be arguing for months about what the beast was going to be. Looking at the painting, I thought, 'If we can do that, that's it.' ''

—Scott quoted in “Death of a Maiden” by Edward Gross, Cinescape November 1997

Scott was so impressed with Giger’s vision that he couldn’t countenance anyone else realizing it. He fought for the extra budget required to hire Giger as the sculptor, and brought him over to the UK. Giger got to work—in his own unique way.

"He took a human skull and jammed it right on the front, riveted it into place and then started modifying it. It was such a beautiful human skull. It had been a real person, not like one of those plastic model kits, and he takes out his hacksaw and he saws the jawbone off and extends it like six inches. He puts an extension on it, and creates this distorted jawbone. Then he starts attaching other fixtures to it and building a new extension on to the back of it. He's doing this to a real human skull. When he finally [finished], a cast was made of it. It was a craftsman who actually cast the rubber costume of Giger's sculpture. When they were finished casting in rubber, he used his airbrush and painted the costume the same way he does his paintings. I truly believe that that monster in Alien is absolutely unique looking. I think it is two strides beyond any monster costume in any movie ever before."

—Dan O’Bannon in Fantastic Films#10 (1979)

The rest is history. Alien opened in 1979 to a rapturous reception: audiences had never seen anything like the Face-Hugger, Chestburster, or full-grown Xenomorph before, a monster that clawed, hard, at their primal fears and repressed memories. Although that human skull at the core of the body suit was never visible, at some innate level, people understood it was there. The monster was both alien and an embodiment of all the horrors of humanity, visualized through a shattered lens.

Over the 45 years of corporate ownership, the facsimiles rendered during the course of nine movies, 38 video games, and countless comic books (from both Dark Horse and Marvel) since, the Xenomorphs have lost their impact. Subsequent filmmakers within the franchise—and many plagiarists—have returned to the depths of Giger’s vision over and over again. Consequently, our fear of the Xenomorphs has been diluted, as their familiar elements override our shock and awe at the once-unknown. In Freudian terms, the creatures are no longer ‘Unheimlich’, but represent the pleasure we derive from our compulsion to repeat. We know the aliens’ life cycle, we have expectations of both their behavior and the plot they drive. Fundamentally, like other movie monsters, we understand they are just a person in a suit. Yet, we still buy tickets.

The Xenomorph—and its continued box office clout—should teach us that audiences crave monsters which originate in Art, in an individual’s heart-stopping vision, rather than respawning themselves from over-used IP. Yes, I’m sure I’ll enjoy the ride offered by ALIEN:ROMULUS this weekend, but really, truly, I yearn for a new monster for unlikely heroes to battle, an original yet no less idiosyncratic rendition of our shadow selves.

So now I know where the inspiration for Alien came from. Fascinating - if somewhat gruesome - backstory to Giger’s depiction. Classic Karina Wilson writing!