The Hollywood Dream (4): Proto-Monopoly At The Hotel Hollywood

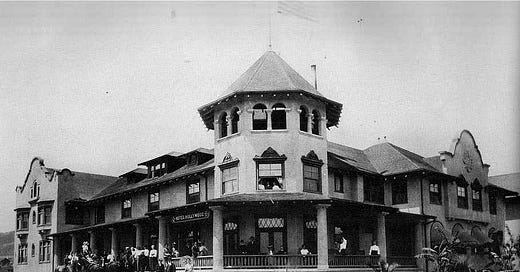

Our first wander through the dreamscapes of the Hotel Hollywood, sadly demolished in 1956, won't be our last.

As any Monopoly player knows, adding a hotel to your property is peak capitalism. It’s a power move, meant to inflict pain on rivals and establish your dominance over the board.

Long before the Monopoly game hit the market (1935), H.J. Whitley understood the tactical benefits of constructing a hotel in a new township. It was a key component of his Hollywood dream and a major investment, with two partners, fellow Los Angeles Pacific Boulevard and Development Company board members, George W. Hoover and General Harrison Gray Otis. The Los Angeles Times featured an architect’s sketch of the planned frontage in the “House and Lot” real estate roundup on Sunday 22 June, 1902. The Times enthused over the “handsome hotel”, with its “latest and most scientific” heating and plumbing. The “two story cement and plaster building in the mission style” had red roofs and white walls, fifty guest rooms (including some with en suite bathrooms) and plenty of space for expansion. “The house, when finished, will be a conveniently arranged and comfortable hotel, and its exceptionally fine location will doubtless make it popular.”

The hotel, on the northwest corner of Highland and Prospect (later Hollywood), was modest by Gilded Age standards. It was a country resort surrounded by citrus trees, as opposed to the faux castles and palaces nestled amid formal gardens being constructed on the East Coast. However, the accommodations offered were far more sophisticated than others in the area. The Sackett Hotel, built in 1888 to the east at Prospect and Cahuenga, rented rooms above the post office and store to traveling cowboys. The more-genteel Glen-Holly Hotel at Ivar and Yucca, opened in 1895, had twenty rooms, but just one bathroom.

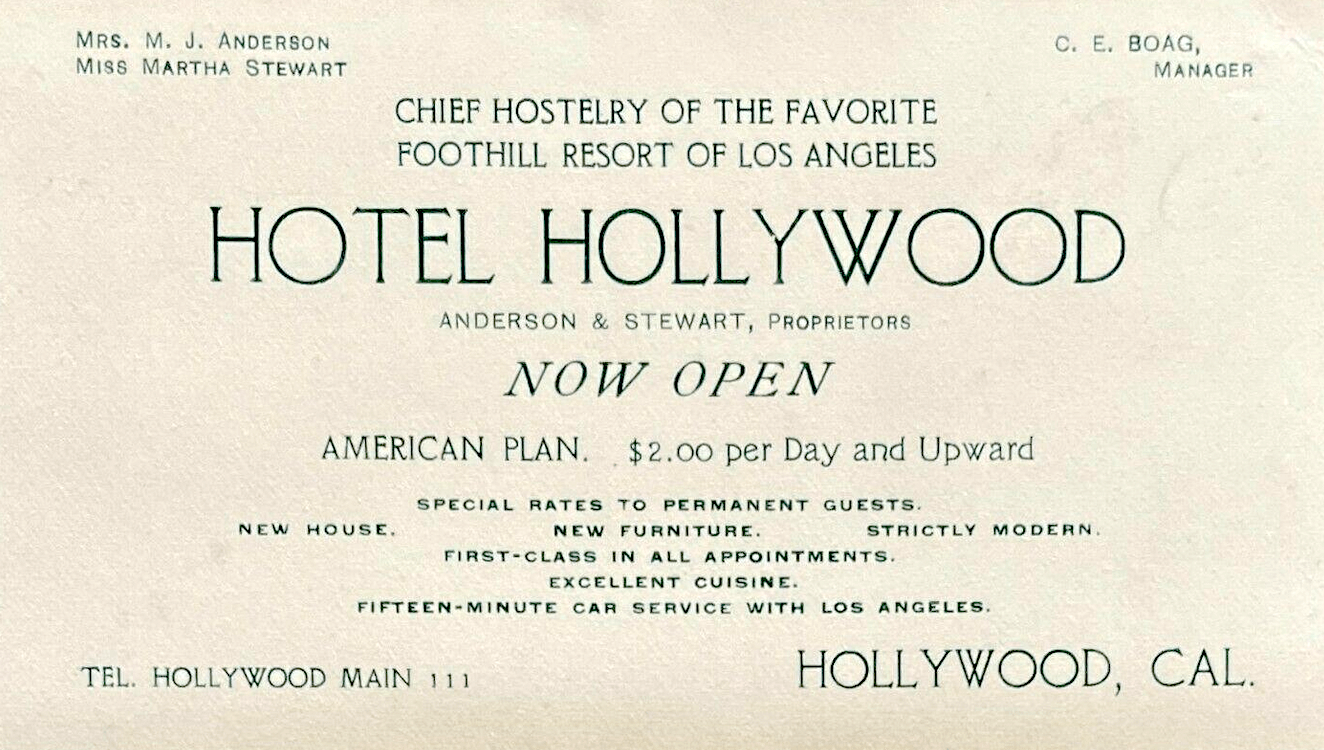

Whitley had an entirely different clientele in mind. Dennis and Farwell’s architectural design incorporated a rotunda and grand staircase, and on-site amenities included an ice station, a children's dining room, and barber shop. Whitley personally oversaw the interior decor, utilizing high quality antiques and oriental rugs—from the same international suppliers who stocked his store downtown. He also finessed the design of the hotel stationery, because (as he wrote to his business partner, Otis) “It will be very largely distributed throughout the world, and is one of those trivial things by which people judge the artistic standards of the Hotel.”

Those “artistic standards” were crucial. The hotel presented a prototype for Whitley’s Hollywood dream: an abundant life lived amid understated Mediterranean elegance, complete with all modern conveniences, such as electric lights, telephones, and a regular streetcar service. If you, too, wanted to live that dream, inside that aesthetic, all you had to do was buy a lot from Whitley, build a mansion (costing no less than $3000), and invite yourself to the perpetual party at your friendly neighborhood hotel.

The festivities kicked off on December 18, 1902. The Hotel Hollywood flung open its doors with a “complimentary banquet” for more than a hundred well-heeled guests driven in from downtown Los Angeles. Most of them owned stock in the LAPBDC. It was a night to remember. The hotel itself, “resplendent with lights…charming with decorations of ferns, plants, and carnations” served as a backdrop for a full evening of self-congratulatory speeches.

Various board members regaled (according to the Times) their fellow guests with toasts titled “How To Develop Suburban Boulevards” (from Col. G.J. Griffith), “How To Build Railroads” (Gen. M.H. Sherman), “How It Feels To Run for Office” (Mayor of Los Angeles, M. P. Snyder) and “How To Get Money Out of a Bank Easy” (W.C. Patterson). Sounds like a good time, especially as everyone had to sit through the speeches sober–Daieda Wilcox (now Beveridge)’s continuing influence meant the guests could only imbibe non-alcoholic beverages.

Daieda was still invested in her dream of an abstinent Christian community. After Harvey’s death in 1891 she remarried, a handsome Midwesterner Philo Judson Beveridge, son of the governor of Illinois, in 1894. Together they set up Beveridge and Beveridge Real Estate, in an office on the corner of Prospect (yet to be renamed Hollywood) and Cahuenga and continued to sell off lots from the Wilcoxes’ original tract. She opposed Whitley and Co.’s plans wherever she could, donating land to raise churches, schools and a library––and win local residents’ votes. She enforced the no liquor rule, and also supported bans on firearms, fast cars, bicycles and tricycles, pool halls and bowling alleys within the subdivision. Anything to discourage undesirables from visiting. But she was fighting a losing battle. She was no match for Whitley’s political flesh-pressing and, as a woman, couldn’t even vote against the measures the LAPBDC pushed through, allowing more and more development. And, as she didn’t own a hotel, she was limited to hosting local dignitaries at her farmhouse.

It wasn’t enough. Daieda’s Hollywood dream officially expired on November 14, 1903, not quite a year after the Hotel Hollywood opened. Whitley’s campaign in his dining and ballrooms paid off when he facilitated an 88-77 vote of local (male) residents for the incorporation of the city of Hollywood. With Whitley and his cronies in control of the Board, it was game over for the rival landowners who resisted his vision.

In the years following, the day-to-day running of the establishment was the responsibility of widow Mrs. M.J. Anderson and her business partner Miss Martha Stewart. Whitley, impressed by the women’s reputation for catering dinners and weddings, gave them a seven year lease and permission to go for it. They turned the Hotel Hollywood into a social focal point for residents and tourists alike and oversaw its expansion.

The wraparound porch, with its ocean views and breezes, welcomed wealthy Midwesterners who wanted to spend the entire winter in balmy Southern California. Anderson and Stewart invited them to mingle with local guests at the glittering suppers, art exhibitions, and concerts they hosted for up to 300 pax, many of them commuting from Los Angeles on the Balloon Route streetcar. Of course the Midwesterners fell in love with the area and wanted to stay, which proved very profitable for the ongoing real estate operations of Whitley and Co.

Whitley had no interest in running the hotel long-term. In 1907, frequent visitor Mira Hershey took control of the stock holding company. The chocolate and lumber heiress was entranced by the hotel on a day trip from her Bunker Hill mansion and made it her mission to become the outright owner. She would make it her main residence and indeed died in her room there in 1930. Meanwhile, transformation was coming. During the Hershey years, the hotel evolved beyond Whitley’s capitalistic vision into something glamorous and storied. Like other elements built on and around Ocean View Tract, the hotel outsoared its original commercial purpose and manifested its own Hollywood dream, shepherding in the birth of the film colony.

But that comes a little later. Don’t worry, we’ll be back through these doors as there is so, so much more to tell. First, however, let’s take a short detour into the lands of the dead.