Maila Nurmi's (a.k.a. Vampira) Slow Rise (Part One)

In March, we celebrate Women in Horror. Which brings us to a two part exploration of the peerless Maila Nurmi.

“Icon” is one of modern culture’s glib, go-to words, tossed casually into sentences so often that it’s lost its power. True icons aren’t just distinctive or memorable people, they’re visual representations that inspire awe. We look up to these star personae, admire their talents and achievements, and aspire to be like them. “Icon” is a word often applied to those who have successfully traversed the Hollywood Dream, the rags to riches metamorphosis that, it’s widely assumed, turns fame and recognition into a lifelong revenue stream.

Except when it doesn’t.

There are many former icons out there, working construction, stacking retail shelves, shilling home appliances, even preaching. Some welcome obscurity, some are ill-equipped to cope. Fame, so sweet in the moment, leaves a bitter, and lifelong, aftertaste. It takes more courage and resilience to navigate these post-fame years than it does to face the flashbulbs–especially as these miles along the Haunted Path are traveled alone and lonely, with reps and entourages long gone.

Maila Nurmi struggled for years to earn her brief season in the spotlight and those few months of glory were followed by a decades-long downturn. Yet she clung to her Hollywood Dream, remaining within the golden valley even when all she could afford to rent was a concrete-floored garage. She was a born artist, a true creator, and although she took on menial jobs to support herself, she couldn’t be, do, or live anywhere else but the 90028. And, in the end, it worked out. She died having reconnected with the community who valued her and her creativity. A true Hollywood ending, if you will.

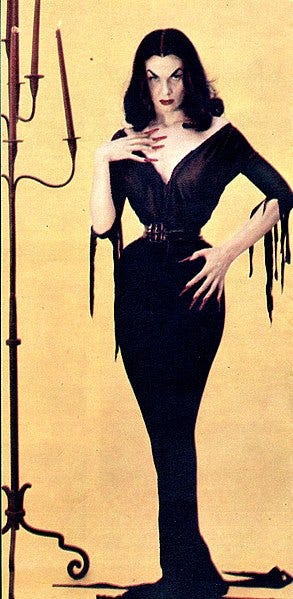

In the wider world, Nurmi is mostly remembered for the character she created. Even if you don’t think you know Vampira, you know Vampira. She was the original horror host, who appeared on Saturday nights on KABC for just 11 months. During that time, she tapped into the national zeitgeist, spawned countless imitators, appeared in LIFE magazine, and prowled the streets of Los Angeles in full pancake makeup and waist trainer, scaring children from the back of her rented hearse. Vampira was pure performance art, as Nurmi mapped macabre detail over the top of the ‘perfect housewife’ template to create a subversive, seductive, and cynical avatar. The power of her image endures today, selling t-shirts, mugs, pins, and all manner of merch emblazoned, and dolls manufactured to her famed 38-17-36” proportions.

Vampira stands as a synthesis of pop culture womanhood from the first half of the 20th century. Her DNA twists through the vamps of silent film, the mysterious and sexually charged screen sirens who used their power to exploit and dominate weak men, wraps around the then-unnamed matriarch of the cartoon Addams Family, then spirals through the haughtily-proportioned pinup girls created by Alberto Vargas and the stiletto-heeled dommes of the underground fetish scene. Deeper than that, she evoked goddesses of death and the underworld: Kali, Maman Brigitte, Hecate, the Morrígan. Nurmi herself said Vampira was “one part Greta Garbo, two parts each of the Dragon Lady, Evil Queen and Theda Bara, three parts Norma Desmond and four parts Bizarre magazine”.

Nurmi debuted Vampira at the Bal Caribe costume ball in 1953. Inspired by the “ghoul girl” look of Charles Addams’ creation, Nurmi hand-stitched a dress, rented a wig, painted her face grey, went barefoot, and adopted a flat, zombified affect. She stayed in beyond-the-grave character all evening and was a huge hit with the guests, winning the first prize (a portable radio) in the costume competition. A TV executive, Hunt Stromberg, was particularly impressed by her performance and tracked her down a few months later when he was programming Saturday nights on local TV station KABC.

In 1954, television was still very much establishing itself as a home entertainment medium and needed more content than it could produce. Bundles of mystery and thriller B-movies, churned out by studios in the 1930s and 1940s and packaged for a rock bottom price, were perfect for filling the late-night slot—which was only watched by weirdos and insomniacs anyway, unable to tear themselves away from their fuzzy 15” screen long after decent citizens had gone to bed. Rather than simply dumping these movies into the schedule, Stromberg thought it would be better if they were introduced by a host, someone who could present the often-creaky narratives with a wink and an apology, as well as offering new, live content every week. So he reached out to Nurmi.

It was the opportunity she’d yearned for, a potential ‘golden elevator’. At 31, she feared her career was going nowhere.

When she first arrived in Los Angeles in October 1941 as a fresh-faced teen fleeing drudgery in the fish factories of Astoria, Oregon, she never thought it would take this long to earn a good living. She was already a dreamer, who survived her isolated childhood by diving deep into the world of comic books. But the travails of her favorite character, the pirate queen Dragon Lady, couldn’t prepare her for the struggles that lay ahead. Over and over again she’d find herself girding for battle — against poverty, and against predatory and exploitative men.

She had to face down slavering carnivores during her first months in Hollywood, men who posed as showbiz agents as a cover for their sexual assaults. It made her reluctant to pursue acting as a career and she diverted to sales jobs. But she was still a knockout, enough to attract all the wrong types of attention. A couple of years later, she ran into her hero, Orson Welles, in Musso’s. He took her back to his West Hollywood bungalow and took her virginity. They began a brief, clandestine affair, which ended abruptly when Welles married Rita Hayworth—and twenty year-old Nurmi discovered she was pregnant. Welles failed to respond to her messages. Supported by her parents she had the baby in secret, in New York, and gave him up for adoption.

After giving birth, Nurmi spent the rest of 1944 jumping from odd job to odd job, finally snagging a part in a Mae West show on Broadway, “Catherine the Great”. She didn’t last long: she was fired (she claimed) for upstaging the star. She also appeared for one night only as a dancing and screaming skeleton in “Spook Scandals” in December, long enough for her friend Irving Hoffman to write a rave review: “Mila Niemi [sic] is Hollywood’s answer to every dream”. The Broadway to Los Angeles wires began thrumming, and Nurmi took the next train West.

None other than Howard Hawks wanted Nurmi to play the female lead in a horror movie about a sinister Eastern European countess luring innocents to her Gothic mansion. William Faulkner adapted “Dreadful Hollow” from the novel by Irina Karlova (the Slavic-leaning pen name of the Anglo-monikered Helen Mary Elizabeth Clamp), amping up the vampire’s Sapphic eroticism and transforming what could have been simple B-movie material into a layered and subtext-heavy screenplay. It would have been the perfect role for Nurmi, a launchpad for genuine stardom, and the film could have been a worthy successor to “Dracula’s Daughter” (1936) within the horror canon. Alas, Hawks treated her like all his other starlets, messing her around with meetings that went nowhere, poking at her looks, telling her to “fix your teeth”. Enraged, Nurmi tore up her contract in front of him and tossed it onto his desk on her way out.

An epic flounce, but a complete self-own. This level of opportunity would not come around again.

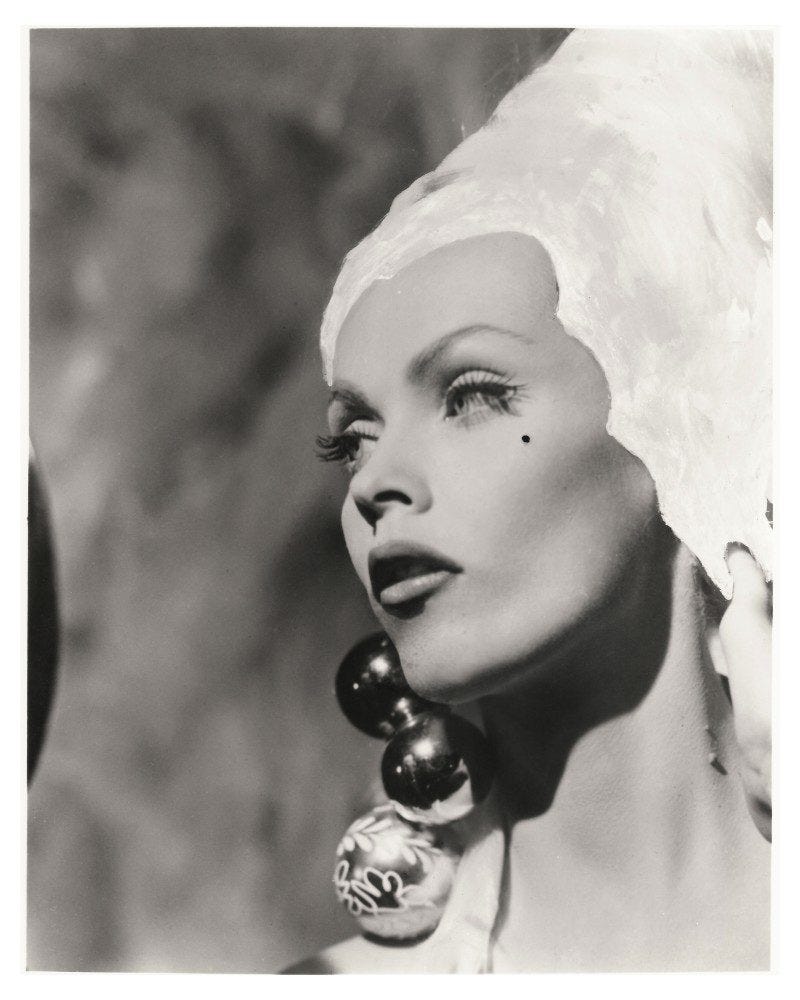

Over the next few years, Nurmi pursued a performance career. She danced onstage at the Florentine Gardens and Earl Carroll theatres. She pursued pinup modelling too, a burgeoning genre during the war. After leading glamour photographer Bruno Bernard (he shot the iconic image of Marilyn Monroe’s white dress flaring over a subway grate) rejected her for carrying too much weight, she got herself hired as his assistant and learned about appealing to the male gaze via make-up, lighting, poses, and costumes: the art, as opposed to the flesh, of a top model. She met Marilyn in the studio, then still plain Norma Jeane Dougherty. Nurmi remembered her as “like a wounded animal… nervous& wary… I felt she knew how to pose while showing off those knockers of hers to best advantage & still maintain that little girl lost look. But she was a lovely woman. And as it came to be, tragic.”

In 1948 Nurmi began a relationship with former child star turned writer-director, Dean “Dink” Eisner. They lived over the brush (as my grandmother would say) in Laurel Canyon. Nurmi worked as a hat check girl to pay the rent, so Eisner could focus on writing his next hit. For a while, they existed in unwedded bliss, welcoming rescue animals into their home. Nurmi relished being “someone’s very precious private woman” and “secretly vowed to be the BEST WIFE that EVER LIVED.” She remained insecure, however, and felt particularly threatened by images of Eisner’s ex-girlfriend, swimsuit model Barbara Freaking. She embarked on a near-starvation diet, a brutal exercise program, and slathered meat tenderizer (papaya powder) on the flesh around her middle. The effects were rapid: a 30lb weight loss and “several inches” off her waist.

Armed with her new measurements, Nurmi approached the pinup painter Alberto Vargas. Vargas dealt in icons, glamorous and sexual airbrush paintings of women who adorned movie posters and magazine covers and ended up replicated as nose art on WW2 fighter planes. He declared she had a “wonderful body” and included her, briefly, in his top 10 beauties. This was enough to get Bruno Bernard to rethink his negative opinion and he cast Nurmi alongside a bikinied Lili St. Cyr, Irish McCalla, Joan Olander (later Mamie Van Doren), and Norma Jeane in his “Beauty on the Beach” movie which, despite the stacked cast, is no longer available. Nurmi said “It… was not made for general release but for the mail order trade, you know, the home masturbation market.”

During the late 1940s and into the 1950s, Nurmi adorned magazine covers and calendars. But it wasn’t enough. She dreamed of dedicating her life to rescuing abused animals, and toyed with the idea of becoming a famous evangelist to fund this endeavor. She was intrigued by the new medium of television, and considered creating her own comedy show, a parody of the ‘perfect family’ soap operas proving popular at the time. She loved the macabre Charles Addams “Homebodies” cartoons in the New Yorker, and thought she could bring a similarly satirical vibe to TV. So, when her friend, rising fashion designer Rudi Gernreich suggested she walked at the Bal Caribe to raise her profile among TV execs, Vampira was born rose from the grave.

Hunt Stromberg’s job offer seemed like the chance she’d been working and waiting for, but it only paid $75 a week. Nonetheless, Nurmi embraced the role with gusto, parading in her Vampira costume on and off the attic set and engendering the legend. For a few months she stood atop her world, a dark goddess incarnate, loved and lauded (she was even nominated for an Emmy). Then, as Hollywood Dreams often do, it all came crashing down.

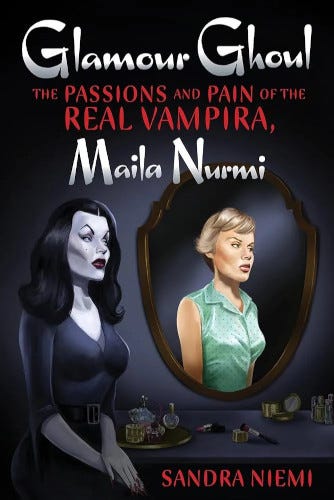

If you need more Maila before then, I highly recommend her niece Sandra Niemi’s 2021 book, Glamour Ghoul:

You can also hear me talking about my veneration of Maila in the latest edition of Haunted Hollywood Hour with Carly Heath, at Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

If you enjoyed reading, please drop a ❤️ or leave a comment. Thank you 🫶🏻

Great piece. I remember being transfixed by Elvira when I was a kid. She was the next generation Vampira.

She is back from the dead in this piece, thank you Karina.