Maila Nurmi's (a.k.a Vampira) Tortuous Fall (Part Two)

Her brief fame had a long and troubled tail.

We left Maila Nurmi in April 1954. She’d just accepted what seemed like the offer of a lifetime and, on Saturday 30th April, she made her television debut as ‘Vampira’ - a name coined by her husband Dean Eisner. This character had evolved significantly from the ‘ghoul girl’ costume of the Bal Caribe. She was now a vampire rather than a zombie, deep-voiced and articulate, flirting coyly with the camera as she discussed recipes and home decor tips. Just like any other TV housewife.

Her shows were broadcast live, which means they were never recorded in the “kept for posterity” sense of the word. Television was still in its infancy, considered gimmicky home entertainment rather than an important historical medium. The Vampira Show was the lowest of local lowbrow low cost entertainment, requiring only the budget for the main character, a black box studio, swirling dry ice, a pun-spewing writer, and bargain bin Halloween props. Her salary was $75 per week ($885 today), as KABC valued and paid her as the televisual equivalent of a sign spinner. She attracted sponsors and introduced cheapo B-movie after-midnight filler content. Why, the suits reasoned, should they bother saving any of her performances?

A lesser artist would have phoned it in. Nurmi gave it her all, paying for her own hair, make-up and costume and, initially at least, doing the four hour prep at home before riding the bus to the studio. Her Saturday night performances began a day or so earlier with a process she described as “body sculpting”: fasting, steam baths, and papaya powder. She swabbed her waistline with the supposedly meat tenderizing particles, encased her midsection in a rubber inner tube, and let it consume her flesh overnight. Week in, week out, Nurmi discarded her scruffy (and often smelly) pants and outsize sweaters, hid her tousled short blonde hair under a wig, and stepped into Vampira’s unique silhouette, ready for the close up of her signature, orgasmic scream.

It was an ascension of sorts, the claiming of a throne. Vampira melded the coded innuendos of 1930s Universal horror with 1950s sitcom humor and rendered them as an arched eyebrow, high camp cocktail. She welcomed visitors to her attic with housewifely concern, aping the mannerisms if not the materialism of contemporary domestic goddesses Harriet Nelson, Donna Reed or Lucy Ricardo. These women also constricted themselves inside girdles, heels, and facepaint, but where they were designed to soak in the male gaze, Vampira deliberately defied it. She turned her exaggerated pin-up proportions into a grotesque sight gag and her barbed mariticide one-liners aimed to shrivel desire, not inflate it. She was the solo queen of her domain, outside the patriarchy, existing in a place where Father Didn’t Know Best, there was no Making Room for Daddy, and Leaving It To Beaver was out of the question. Whole not wholesome, she completed herself.

Mercifully, a KABC promo of the show’s opening sequence was recorded for repeated broadcast, and hints at the delights in store for late-night Angelenos in 1954.

You have to imagine what happens next. But here’s Maila herself talking about a typical foray into Vampira’s Attic.

Nurmi was riding high in the summer of 1954. Vampira attracted international attention. Dennis Stock photographed her for a Life Magazine spread. She was given access to the Hollywood ‘in’ crowd, invited to be a guest on The Red Skelton Show and put on the list for premieres and parties.

She first saw James Dean at the premiere for Sabrina in September at the Paramount Theatre in Hollywood (before that and again now the El Capitan).

“Here comes this guy in a tux with Howard Hughes’ whore on his arm [Terry Moore]. She had a loopy smile on her face, clearly enjoying the attention, but he is mad. It was obviously a studio date. He is angry to have to be there, and he certainly doesn’t want to be with her. And I knew, I had to meet this guy.”1

The following afternoon at Googies coffee shop (at Sunset and Crescent Heights) the same guy roared up on a motorcycle. Nurmi recognized him instantly. There was an immediate connection–later that afternoon, Nurmi rode away on the back of Dean’s motorcycle.

We were psychic twins, Jimmy and I. Both of us were misunderstood in a world of strange beings. When at age 31 I met Jimmy, he was the first entity of my own species I’d ever encountered. When at 23, Jimmy met me, he thought he’d at last met someone from his own planet. We became instantly glued to one another – our psyches melded.2

The timing and power of their connection, like so many other events in Nurmi’s life, seems both fortuitous and star-crossed. Jimmy was in the last year of his life, she wasn’t even halfway through hers, but they shared a fascination with death and matters beyond the material. Their bond was spiritual, not sexual. Jimmy’s mother died of cancer when he was just eight years old, leaving her sensitive, violin-playing son searching for the divine feminine. For a few months, it seemed as though he’d found it in Nurmi.

For me, Jimmy seemed a mirror of my psyche, and Googies was the womb in which we lived as Siamese twins, the endless stream of coffee our placenta. Sure, we sometimes ventured away from there, but the environment outside the womb was hostile to fetuses. 3

When they met, Nurmi was a household name and Jimmy was a rising star, with only one major, at that point unreleased, movie role (East of Eden) on his resume. Along with bit-part actor Jack Simmons, they formed a trio nicknamed the Night Watch by fellow Googies regulars, because of their macabre shared interests. Nurmi recalled riding round in Simmons’ converted hearse in the witching hours, sneaking into graveyards and even morticians’ offices. Jimmy, a risk-taker who relished pushing against taboos, was usually the instigator, daring the others to trespass, shoplift, and worse.

Life lived partly as Vampira was good for Nurmi. She wore the costume a lot outside the studio, showing up at Googies after shows and personal appearances in full Goth garb. In many ways it was easier to face the world as Vampira, with her confidence, wit and talons, rather than as scruffy outsider Maila, with her secrets and failures in tow.

It was too good to last.

KABC, who owned 49% of the character, wanted to syndicate, visualizing a homegrown Vampira hosting midnight movies in every territory. Nurmi disagreed: she was the one and only. She wanted, rightfully, more money, and to be able to cash in on personal appearances. KABC refused to negotiate. The final straw came when Nurmi was invited to guest as Vampira on NBC’s George Gobel Show, a huge opportunity to reach a national audience. Unfortunately, this presented a time clash with The Vampira Show. KABC forbade her from participating. On Saturday, April 2nd 1955, she appeared anyway, delighting millions with her Vampira schtick in a range of comic sketches. It presented the brilliant high point of her career–and, thankfully, was preserved on kinescope, resurfacing earlier this century.

That was it. After months of FCC complaints about the show, a rising scandal around the break-up of her marriage to Dean Eisner, and the rumors about the Night Watch, KABC were done with Nurmi. The following Tuesday, producer Selig J. Seligman offered to buy Vampira outright. When Nurmi refused, he fired her. She was devastated. Her mother found her wailing in the bathtub, head shaved, every mirror in the apartment smashed to pieces. Although her friends, including Marlon Brando (who recommended psychotherapy) rallied round her, her life had changed, irrevocably.

April 1955 was the cruellest month for Nurmi in other ways. East of Eden premiered on the 10th, shooting James Dean into the cultural stratosphere and beyond her reach. In the fall of 1954, Warners had got wind of their hot new star’s proclivities (possibly thanks to blackmail attempts by Dean’s one-time lover, Rodgers Brackett) and wanted to kill any rumors about bisexuality or BDSM that might threaten the value of their nine picture deal. The studio PR machine whirred into life, nixing some of his shadier known associates, Nurmi included. Rent-A-Dagger Hedda Hopper jumped in with an interview in which she asked Dean about the “thin-cheeked actress”. His reply, when Nurmi read it, cut deep.

“I don’t date witches, and I dig cartoons even less. Vampira was merely a subject about which I wanted to learn, and after engaging the girl in conversation, I found out that she knew absolutely nothing and is only obsessed with her Vampira makeup.”4

Despite this apparent betrayal they remained friends, less publicly, and, as Dean’s star rose, less and less. The bond between them thinned, with Dean often unavailable for Googies hangouts. He ditched his illicit sojourns with the Night Watch in favor of hanging out with Nick Ray’s Rebel Without A Cause crew across Sunset Blvd at the Chateau Marmont. Then he was lost forever on September 30th, 1955, another devastating blow for Nurmi.

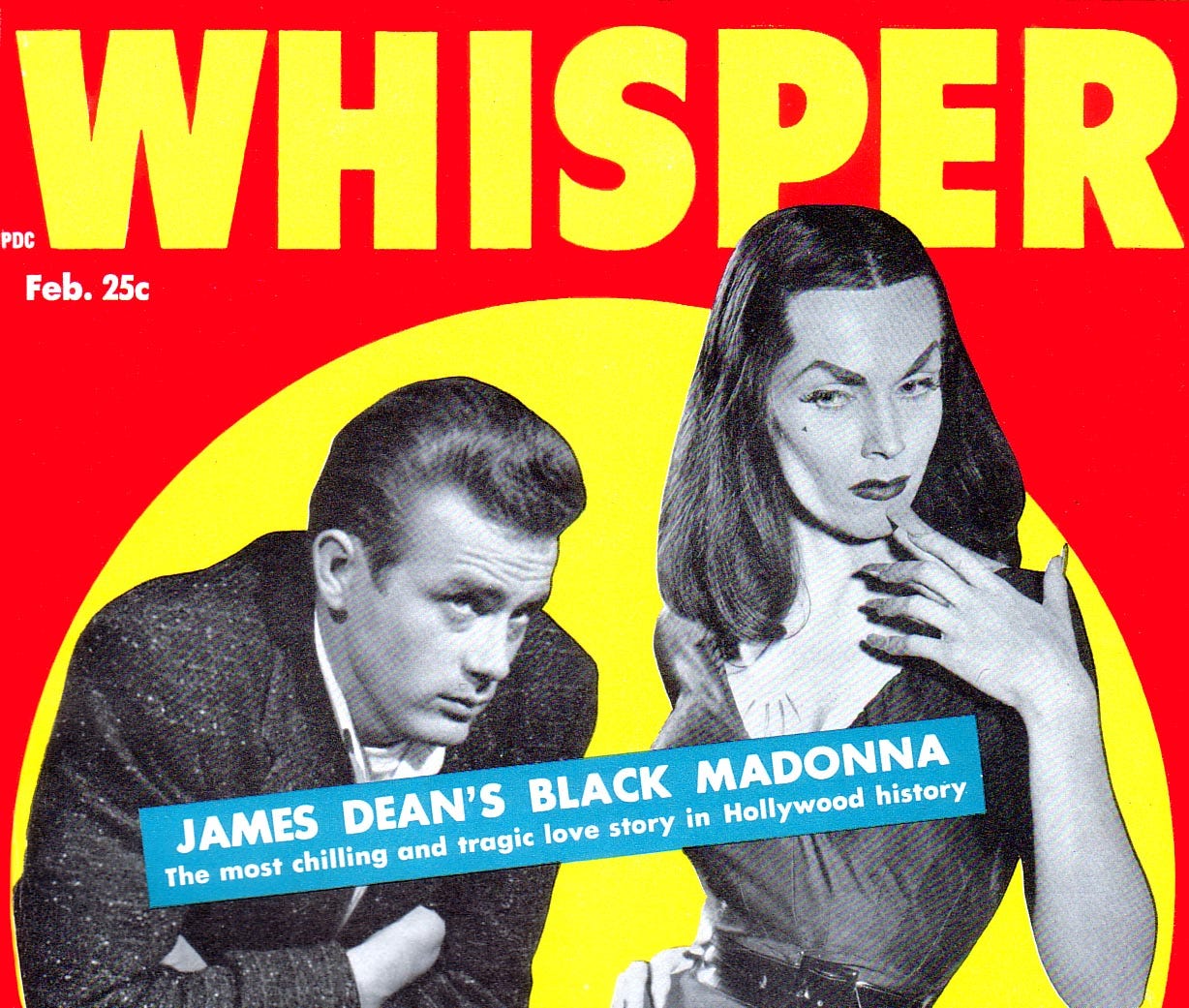

Nurmi drifted. She was contractually forbidden to perform as Vampira for six months after her firing, which was more than enough time for the buzz around her character to subside. She escaped to New York, but the horrors continued. In January 1956, a stranger forced his way into her West 46th Street apartment and subjected her to a terrifying assault. Stripped half naked, she managed to escape and get help. The media swarmed, demanding she pose for photos of her bruises, which they published alongside lurid descriptions of the attack. The following month, Whisper magazine printed a salacious spread about her and Dean, accusing her of cursing him to death. Given that adulation of the dead movie star had reached near-deification levels, it made her persona non grata across Hollywood.

Nurmi faded. She snagged bit parts in movies, a brief stint doing comic bits with Liberace in Vegas, two days work as the model for Maleficent for Disney, but the work was too sporadic to sustain her. Although she initially refused to stoop so low, she eventually accepted $200 from Ed Wood to appear for 15 wordless minutes as Vampira in Plan 9 From Outer Space. After that, nothing. She sank into post-fame, cleaning houses, laying linoleum, eventually opening a thrift store on Melrose named Vampira’s Attic. She scraped a living on the streets she once stalked in her pinup goddess heels, sleeping on the concrete floor of a converted garage.

Yet Nurmi never quite vanished. The community maintained the memory of who she was and held space for her. A few of her famous friends, like Marlon Brando, sent her money sporadically. And in the 1980s, the twentieth century caught up with her bold aesthetic. Local punk banks like The Misfits and Satan’s Cheerleaders found and embraced her, putting her on stage and on vinyl. She was courted for a Vampira comeback, but was eventually passed over in favor of busty Valley Goth, Elvira, and Murni lost the subsequent plagiarism lawsuit. The 1990s were even better, thanks to Tim Burton’s Ed Wood movie pulling Plan 9 back into cultural consciousness. Her least favorite performance as Vampira, the only one on film rather than television, was paradoxically the best preserved, and the one which engaged a new generation of fans.

Maila Nurmi lived her last years in a bungalow court on North Serrano, supported by her friends and by her stake from the online sales of merchandise and memorabilia–back in the days when the Internet was a force for Good. She cherished sitting in the courtyard with her rescue cat and dog, and apparently bought groceries at the same Food4Less that I did, on the one-time site of the William Fox Studio. The Food4Less has since been demolished and a giant new apartment building has sprouted in its place–complete with a Whole Foods. That’s 2020s Hollywood for you, continually overwriting the past.

I didn’t know Maila’s story at the time, but I often wonder if we ever brushed elbows in the produce aisle. If so, I missed my chance to acknowledge a true twentieth century icon, who moved among other icons and in a few short years engendered stories I could share for days–but this is not the place. She truly lived the Hollywood Dream, with all its carnival cruelties. After her star fell, she didn’t physically leave the 90028. Her persistence and loyalty was rewarded by her final resurgence and interviews shot at the time show she never lost her star quality, sparkling for the camera even in her 80s. In the end, like the men who fell under her spell, James Dean, Marlon Brando, Dean Eisner, Elvis Presley, Anthony Perkins et al, she earned immortality.

Maila Nurmi died at home on January 10, 2008 and is of course buried at Hollywood Forever Cemetery. You can visit her there, as so many of us still do.

If you want more Maila, I recommend (again) her niece Sandra’s book, Glamour Ghoul (Bookshop.org affiliate link) and R.H. Greene’s 2012 documentary Vampira and Me (currently streaming for free on Tubi).

Niemi, Sandra (2021). Glamour Ghoul: The Passions and Pain of the Real Vampira, Maila Nurmi. Feral House, p.133

Ibid, p.136

Ibid, p.139

Hedda Hopper’s syndicated column, November 18, 1954